In 2011, executives at Teach For India spent multiple meetings puzzling over a metaphorical jigsaw.

Their organisation had begun life in 2009 with a mission to improve the quality of education for India’s most underserved children. Bright, educated professionals received a fellowship to teach full-time for two years at public and low-income schools. The first batch of fellows was about to graduate, and the TFI team had enthusiastically come up with the analogy of a jigsaw puzzle to better frame their own goal as an organisation. The pieces of the puzzle represented all the variables needed to “provide all Indian children with excellent education”: good teachers, sound infrastructure, access to ed-tech, better government policies, and more.

But there were missing pieces they could not quite define; unidentified interventions without which it seemed difficult to solve the problems ailing the school education ecosystem.

“As our fellows started to graduate, we invited them to make career choices by asking the question, ‘what is the role I can play in solving this education puzzle?’ That was the beginning of our journey towards unleashing the potential of our fellowship’s alumni,” said Ramabhadran Sundaram, a long-time TFI executive who works as the director of its Alumni Impact programme, which aims to impact the education sector as a whole, working at grassroots within schools as well as at the levels of institutions and policy.

When educationist Shaheen Mistri founded TFI, the team knew little about what the future career trajectories of its fellows could be. Mistri was already well-known as the founder of Akanksha Foundation, which conducts after-school tutoring for children from low-income homes, and with TFI she took her intervention directly into schools. The fellowship model was based on the one established by Teach For America in 1989 – getting college graduates and young professionals to teach in under-resourced schools that sorely need better educators for their children.

“Our first few cohorts of alumni found their own ways to continue to serve children, both within and beyond the social sector, some even through roles they had before the fellowship,” Sundaram recalled.

But as the TFI team gained a deeper understanding of the systemic barriers to educational equity, they further recognised the leadership gaps that their alumni could fill across multiple levels of the education system, and further refined the puzzle. There were also other moments of realisation for TFI – “points of inflection,” as Sundaram calls them – that led to the strengthening of the Alumni Impact vertical.

In 2009, they’d started out with 78 fellows placed in schools. Then seven years later, there were around 1,000 fellows in two active batches – but their total number of alumni had risen to 1,100. “This was a tipping point. We became present to the new reality that from now on, we would always have more alumni than fellows, and the story of Teach For India would soon be the story of its alumni,” Sundaram said. “So we asked ourselves how we could increase our time, energy and investment in alumni to better reflect this changing future.”

In the decade since, TFI has chosen to focus strategically on its support to alumni, incubating entrepreneurs in addition to infusing fellowship graduates in the education sector, particularly to serve children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Incubating entrepreneurs

The Alumni Impact project provides organised mentorship and guidance to fellows about to complete their two years of teaching, encouraging them to seek career opportunities in one of three broad verticals: working directly with children or school ecosystems; enabling “transformational outcomes” in schools through teacher training, ed tech, curriculum development, funding bodies and other initiatives; and working in policy or governance to bring about educational equity.

To help alumni get placements in the social sector and allied fields, TFI also conducts two rounds of career fairs every year. In 2024, at least 126 organisations offered up to 800 placements at the TFI career fair, including organisations like the Central Square Foundation, iTeach and The Circle. According to Ashwath Bharath, senior director of movement building at TFI, nearly 86% of fellowship graduates sought work opportunities at the fair. “Overall, I’d say that around 70% of our total alumni remain in the education or social sector,” said Bharath.

The TFI fellowship, which runs in eight cities across India, directly impacts at least 33,500 children every year. TFI alumni, meanwhile, directly impact over one lakh children and indirectly reach around 500 million children across 23 states. Perhaps its most impressive impact comes through the work of alumni who turned to entrepreneurship after their fellowships. Through InnovatED, TFI’s incubation programme, alumni have founded more than 160 organisations so far, each attempting to work on different pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that TFI envisioned all those years ago.

“Teach For India is a discovery learning process,” said Soumya Jain, a TFI alumnus who founded iTeach, an organisation that runs English-medium secondary schools for low-income students in Pune. “Every fellow has their own learnings, and each one feels strongly about some part of the larger education puzzle that they then want to solve.”

We spoke to three such entrepreneurial alumni to learn the stories of their organisations, and the problems they’re solving.

Subhankar Paul – The Unifly Collective

Subhankar Paul had a very utilitarian reason for applying for the TFI fellowship in 2014: it would look unique on his resumé, enhance his leadership skills and help him move up the corporate ladder in his computer science career. The last thing he expected it to do was change the course of his life entirely. But his journey from amateur teacher to a trainer of school principals was an organic, logical one.

It started when, in the early weeks of his fellowship at an affordable private school in Mumbai, Paul had a hard time managing his students’ behaviour in class. “So I started innovating, taking the children to the field and using cricket scores and run rates to teach them maths,” said Paul. His efforts were a success – his students were not only less disruptive in class but also started performing better. Impressed, the school principal offered to support Paul by taking some of his administrative duties off his plate. In the second year of his fellowship, the principal came to him with an idea: introducing cricket for all senior secondary students, and having a school premier league.

“It struck me that I as an individual could only solve problems for a few children in one school. But if school leaders could be empowered to resolve problems better, and if they could then empower the teachers under them, how many more solutions would emerge?” said Paul.

Keen to understand the complexities first hand, Paul briefly worked as an assistant principal at a different school that TFI had just tied up with. By 2018, he had founded The Unifly Collective and began actively conducting leadership, management and skill development training, as well as exposure visits, for school leaders. The workshops are conducted by the Collective’s staff team as well as invited experts.

“Our aim was to support school leaders to build more high-performing schools, by helping them think out of the box,” said Paul. “At our workshops, we get them to name specific problems they would like to address in their respective schools, and help them come up with a workable plan to resolve them.”

So far, the Collective has reached 1.6 lakh school leaders across multiple states through its various programmes. It has conducted intensive workshops for leaders of at least 130 public and affordable private schools in Mumbai, Delhi and other cities.

In Mumbai, school leader Chaitali Shah describes these workshops as “life-changing.” Shah started out as a municipal school teacher in 2007, and in 2021, she was made the principal of one of several new English-medium schools set up by the city’s municipal corporation. While most other schools follow the state board curriculum, Shah’s school is under the national CBSE board – an ambitious plan by the city authorities to provide higher-level free education to low-income families in Mumbai.

“The children who joined this new school had their foundation in the state board, and now they have to adapt to a more difficult syllabus,” said Shah, who is aware of the responsibility on her shoulders to ensure that her students learn to cope. “Many of my students are currently in remedial classes with their teachers because their maths and reading skills are very poor, and one of my smart goals is that they should be completely free of remedial classes by the end of the year.”

Setting “SMART goals” – using the popular workplace rubric to make goals ‘specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound’ – was a valuable lesson from a Unifly Collective workshop for Shah. “I used to have goals earlier too, but I couldn’t figure out how to meet them step by step,” she said. “But smart goals have given me a clearer vision, and I’m showing my teachers how to set their own goals too.”

Manasi Mehan – Saturday Art Class

Manasi Mehan was a final-year psychology student in Mumbai when she sent off a last-minute application for the TFI fellowship. She didn’t give it a serious thought until after she was selected, when she had to choose between TFI and further studies. It was her grandfather’s words that prompted her to pick the fellowship. “This opportunity will change your life,” he had said – and in a few years, she would discover that he was right.

At the municipal school where she was assigned, Mehan found herself doing what many public school teachers tend to do in the classroom – she used the weekly art period to teach reading and writing to her Class 2 students. “I didn’t know how to teach art, and there was a lot to cover in the reading and writing curriculum,” Mehan said.

It was her students who forced her to rethink her casual decision. “They would ask me why I didn’t teach them art. And once a parent also asked me to teach her son art in school, because he was very interested in it but she couldn’t afford private art classes,” she said. “Then I started asking myself if I really knew my students well – and if I was providing them with safe spaces for creative expression.”

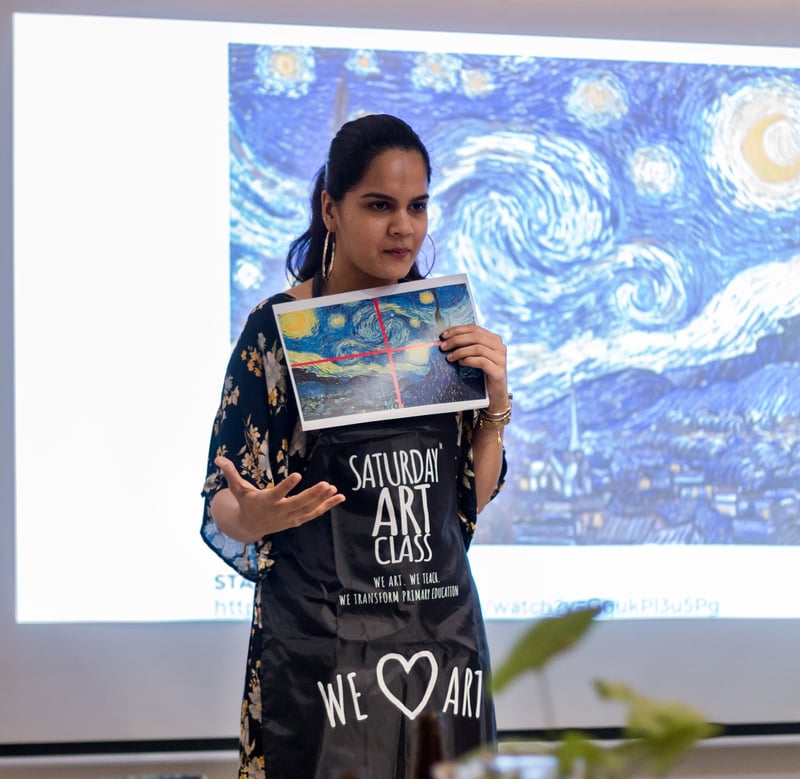

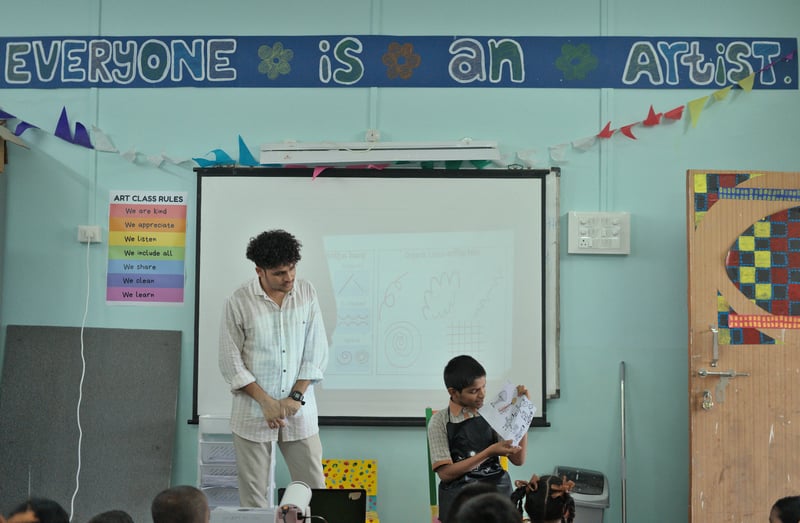

When Mehan finally started art classes at the school, she tried to make it fun, immersive and without rules. In year two, she brought in Chhavi Khandelwal, an architect and artist, to conduct art sessions with the children. Khandelwal began exposing the students to the works of renowned artists from around the world, and introduced elements of social-emotional learning through art.

By the end of the TFI fellowship period, Mehan and Khandelwal co-founded Saturday Art Class, or SArC, as an organisation that conducts art classes in several public schools in Mumbai and also trains educators to become “creative visual arts facilitators”. So far, Mehan’s team has trained nearly 6,000 teachers from low-resource schools in 14 Indian states on how to integrate visual arts and social-emotional learning into classroom teaching.

The name of Mehan’s organisation was coined by her original batch of 30 students. “In Mumbai’s public schools, there is a culture of students skipping school on Saturdays even though it is a working day,” said Mehan, who started conducting her art classes on Saturdays to draw the children in. “They began referring to it as Saturday art class, and the name stuck.”

At the Mumbai school where Mehan first started the art classes, SArC now has its own dedicated art room, decorated all over with colourful art work, where its facilitators run weekly art sessions for students from kindergarten to Class 8. In each session, the facilitator first introduces a new topic, like lines or shapes; and a new artist, say, SH Raza, or Wassily Kandinsky. Children imagine and create their own art based on the themes and styles discussed, followed by a sharing session in which they appreciate each others’ work. Throughout the sessions, facilitators slip in age-appropriate questions and discussions about emotions and a variety of life skills.

While the impact of this approach may not always be obvious, Mehan’s team says they have witnessed positive changes in several children after regular engagement with art. “We had one child last year with a speech impairment, who was always angry and would pick fights with his classmates,” said Priyal Patki, a research associate with SArC. “At first, he would just sit at the back of our art class, refusing to engage. So we would leave paper and art material in front of him and let him observe. By the end of the year, he had gradually moved to the front of the class and started voluntarily collaborating with others.”

Soumya Jain – iTeach Schools

When Jain first heard about Teach For India in 2012, it was the “for India” in its name that called to him more than the “teach”. At the time, he had a job he loved in the United States, working in a home automation company as an electrical engineer. “But I always knew I wanted to return to India someday and work for my own country,” said Jain.

In 2013, he moved back to his home city of Pune and joined the TFI fellowship, teaching English, science and history to Class 6 students at a low-income private school. Jain loved teaching almost instantly, but took time to appreciate the hard work that the school’s principal and teachers were putting in despite a range of bureaucratic and financial constraints that hampered productivity and efficiency.

By the end of the first year of his fellowship, Jain decided he wanted to improve working conditions and incentives for teachers, so that it would in turn improve students’ learning outcomes. This is the shape that iTeach first took – instituting a TFI-like fellowship for small batches of teachers, designing a curriculum for them, and offering meaningful incentives for achieving goals.

While Jain rolled out this version of iTeach, TFI approached him with a parallel opportunity: setting up and running English-medium secondary schools in partnership with the Pune Municipal Corporation. The PMC runs 54 English schools in the city where children from low-income families can study without paying a fee. But these schools only go up to Class 7. For years, students had just two options after passing out – moving to a Marathi-medium public school, or an English-medium private school. Some would be forced to choose a third route – dropping out of school entirely.

“The Right to Education law only mandates compulsory education from ages 6 to 14, and Pune did not have much of a budget to allocate towards secondary education after Class 7,” said Jain, who launched iTeach Schools as a fourth option: free English-medium schools from Classes 8-10, operating from PMC school buildings but staffed and managed by Jain’s organisation.

iTeach now runs nine municipal secondary schools in Pune, and another four English-medium schools in association with municipal bodies in Maharashtra’s Navi Mumbai and Panvel cities. The nine Pune schools aren’t able to absorb students from all of Pune’s English municipal schools, but the organisation tries to ensure that all those who do enroll are given a free and nurturing environment to study in. “At the iTeach school we have the freedom to share our views and ask our teachers anything, and they help us understand our feelings,” said Gargi Darwadkar, a Class 9 student whose parents work as a security guard and domestic worker.

The network effects of the alumni project are deepening. For former iTeach students like Saurabh Kamble, the organisation continues to impact his life. Saurabh completed Class 7 at an English PMC school in 2016 and got the opportunity to enroll in iTeach’s second batch in the nick of time – his mother, a single woman working as a babysitter, was about to move him to a Marathi-medium municipal school.

At iTeach, for the first time, he experienced a school culture without bullying or corporal punishment. “The teachers at iTeach would treat students as equal partners, which really helped to build my confidence,” said Saurabh, now a confident 24-year-old fluent in English. “The teachers focused on both academic growth and holistic growth, but my academic performance improved.”

After school, Saurabh got into Pune’s well-known Symbiosis College to study commerce, worked a number of internships, and is now doing a bachelor’s degree in business administration while working as an admissions associate at iTeach’s “college to career” vertical. Under this vertical, iTeach offers students five years of guidance and support as they transition from school to college and then to work. More than 90% of iTeach students today make it to college, and the organisation aims to make sure that they get well-paying jobs after graduation.

For Saurabh, this job not only allows him to help other students from low-income families access colleges and scholarships, but also helps him earn a living, pay off his family’s debts and support his mother. “If I had gone to a Marathi-medium school instead of iTeach, it would have been very difficult for me to get the kind of opportunities I did.”