Seema Uikey’s heart was heavy when she stuck a large yellow bindi on a poster mounted on her office wall.

The white flex featured a map of her village, Nishan, in the heart of Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara district. It detailed every house, lane, well and public amenity in the area, and was dotted with colourful bindis, placed over a number of houses. The yellow dot that Seema had stuck over the home of the Dhurwe family was not good news. It meant that Rajkumar Dhurwe, just two years and eight months old, was in danger. He’d been diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition.

Seema is an anganwadi worker – a frontline worker appointed under the central government’s Integrated Child Development Services scheme to tackle child malnutrition at the grassroots level. At small, one-room anganwadi centres in villages across India, women such as Seema monitor the health of all children below the age of six, provide them with daily nutritious meals, track their height and weight, and take charge of their vaccination calendars.

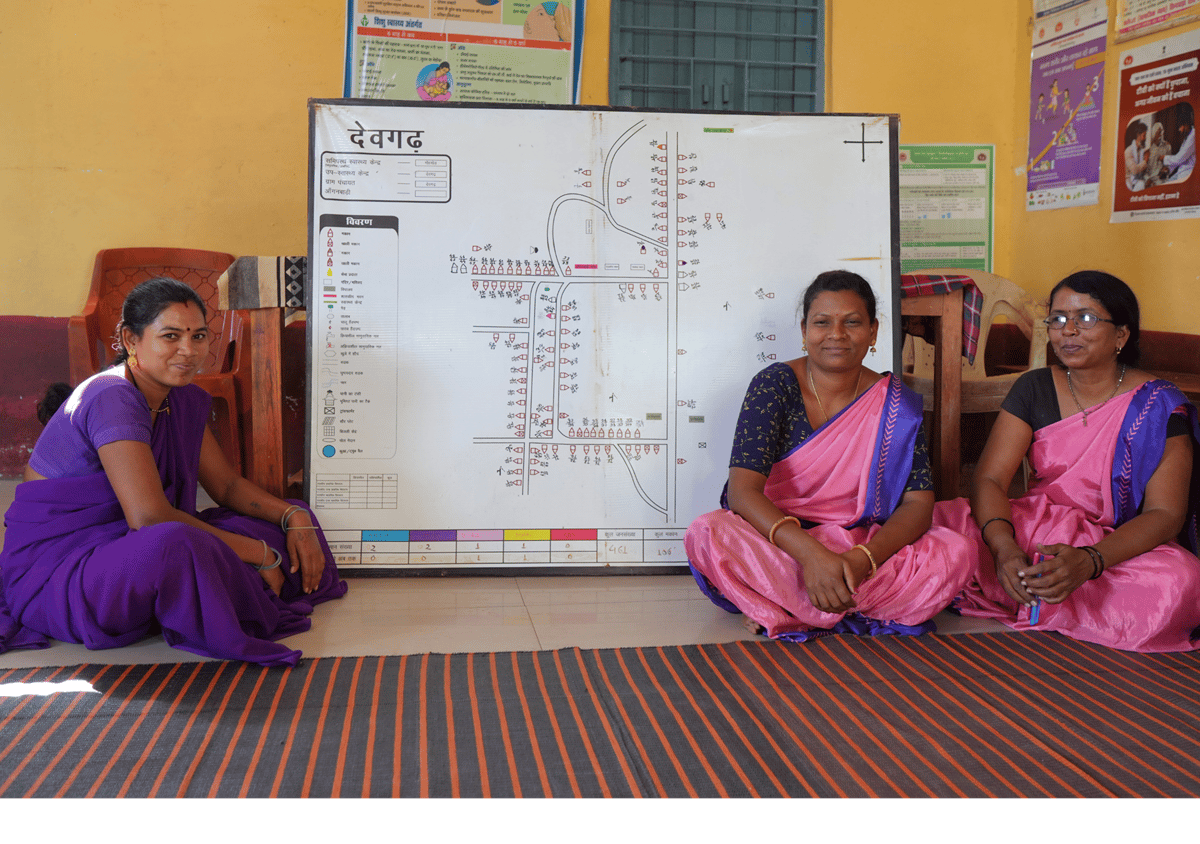

The village map and bindis at Seema’s anganwadi centre aren’t universal yet. They are a unique visual tool designed by The Antara Foundation, an organisation that works directly with frontline health workers to prevent maternal and child mortality in rural India. The maps are one of its many interventions introduced in anganwadis across nine districts in MP, along with a system of coded bindis to help workers keep track of women and children in need. A red bindi, for instance, denotes a child with severe acute malnutrition. Yellow is for moderate acute malnutrition, pink is for neonates, purple for high-risk pregnancies and so on.

Rajkumar Dhurwe’s yellow bindi had been on Seema’s map since the beginning of 2025, and she was determined to see it removed.

The toddler had been in Seema’s care since he was six months old, and seemed healthy up until he was two. When he started to fall sick with bouts of fever and diarrhoea, Seema noticed his falling weight. At two-and-a-half, he should have weighed at least 12 kg, but he was stuck at barely 8 kg.

For weeks, Seema tried to convince Rajkumar’s parents to follow the official treatment protocol for children with acute malnutrition: admitting him to the Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre at the block-level Community Health Centre, where he would have to spend 14 days with a parent until he stabilised. The boy’s family consistently refused to go. “His mother would say things like, ‘Who will work on the farms? Who will do the household chores? My in-laws will never agree’,” Seema said.

So Seema got help. She roped in two other women frontline workers crucial to health services in rural India: the Accredited Social Health Activist, locally known as the ASHA didi, and the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife or ANM.

ASHA workers are community health activists under the National Rural Health Mission, serving as the first point of contact for the health needs of rural populations, particularly women and children. They raise awareness about good health practices, provide basic medication when needed, and help people access primary health services. ANMs, meanwhile, are nurses trained to provide care for mothers and newborns. They work at sub-health centres serving 5,000 people each, across three or four villages.

Together, anganwadi workers, ASHAs and ANMs form the backbone of public health at the grassroots level, particularly for maternal and child health. In different ways, all three are responsible for safe pregnancies and deliveries, preventing infant and maternal deaths, and ensuring that young children are well-nourished, immunised and healthy. But co-ordination between these three roles isn’t always a given.

Anganwadi workers are appointed by the Ministry of Women and Child Development; ASHAs and ANMs come under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Despite the complementary nature of their work, they tend to work independently, maintain separate and often mismatched reports about the same populations, and in many parts of India, don’t communicate effectively with each other.

This was the situation in Chhindwara too, up until The Antara Foundation began working there in 2019. Under its flagship ‘AAA’ platform, anganwadi, ASHA and ANM workers are trained to work together, meeting regularly to share information, plan activities and jointly intervene in difficult cases like that of Rajkumar Dhurwe.

Seema and her ASHA and ANM colleagues spent nearly two months visiting the Dhurwe family, urging them to take Rajkumar to the NRC. “We told them the government pays two weeks of wages to the parent who stays with the child,” said Draupadi Dhurvi, the ASHA worker. If untreated, Rajkumar could slip from moderate to severe acute malnutrition, which could be fatal. “But some people don’t take us seriously, they think inka toh yahi kaam hai – that we are just women with no other work.”

When these arguments persisted, the AAAs of Nishan asked Antara’s field coordinator, Aman Tiwari, to intervene by playing the card of an outsider with authority. “Together, we insisted that the Dhurwes give us in writing that they choose not to go to the NRC and if anything happens to the child, the family alone would be responsible,” said Tiwari. That did the trick, and Rajkumar was finally admitted for treatment and rehabilitation in March. He now weighs 9.6 kg – still underweight but stable and on the road to recovery.

The yellow bindi on Rajkumar’s house will soon be removed, marking a small victory for the AAA workers’ efforts and for Antara’s work.

A model for early intervention

Antara was founded in 2013 by Ashok Alexander, who had already helped change the public health sector in India. As the head of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s India office between 2003 and 2012, Alexander created and ran Avahan, the national HIV-AIDS prevention programme. In the years he spent travelling through rural India and interacting with sex workers affected by HIV, he realised something important: that people within a community know best how to solve the problems affecting them – what they need is someone to listen to them and support them with resources.

“Very early on, I realised that we relied heavily on women on the frontlines, both victims and [health] service providers,” said Alexander. Part of the Avahan model involved removing the social barriers women faced so that they could be empowered to solve their problems. “I thought, can this model be universal? Can it be applied to other public health challenges?”

Addressing the poor state of maternal and child health felt like an obvious choice – from what Alexander had observed in the field, it is “one of the biggest calamities in the country”.

In 2013, India’s infant mortality rate (IMR) was 40 deaths per 1,000 births, as against 33 in Bangladesh, 12 in Brazil and 11 in China. The numbers were complicated when broken down state-wise: states such as MP and Assam had IMRs as high as 54, compared to an MMR of 12 in Kerala and 21 in Tamil Nadu.

The national maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in 2011-13 was 167 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births – more than five times the MMR in China, which was 30 at the time. Here too, states like Assam and Rajasthan reported numbers as high as 300 and 244 respectively, while Tamil Nadu and Kerala had MMRs of 79 and 61. According to data provided by Antara, nearly 50 lakh children under the age of five and 2.8 lakh pregnant women in India die every year of preventable causes like respiratory infections, preterm births and haemorrhage.

Antara’s vision was to prevent, rather than just treat, maternal and child health problems by working with state governments and strengthening public healthcare systems at the grassroots level. In 2015, the organisation piloted its work in association with the Rajasthan government, and started listening to the public health workers closest to the women and children of the community – the ASHAs, anganwadi workers and ANMs. They found that discrepancies in their areas and methods of work added a layer of complication to already difficult jobs.

For instance, the anganwadi and ANM workers’ official registers for children’s vaccination schedules often had incongruent dates and differing lists of names. As a result, beneficiaries would sometimes get delayed immunisation services, or miss out entirely. Their communication gaps meant that important information about high-risk patients sometimes went undelivered.

“For example, if I as the ANM don’t inform the anganwadi worker that I have found a pregnant woman in her village to be anaemic, then she will never know that the woman needs more frequent home visits and additional nutrition,” explained Devki Bhalavi, an ANM worker in Chhindwara’s Tamia block.

The AAA workers are the first point of contact for pregnant and lactating mothers to interact with the state healthcare system. “How can the system consistently deliver quality care in remote places if AAA workers rarely speak to each other?” Chandrika Bahadur, Antara’s CEO, said.

Antara sees its AAA platform as a “starting point” to address such lapses in communication and service provision. It involves fixed monthly meetings in each village between the three women and the female community health officer who works at the sub-health centre, often in the presence of a field coordinator from Antara who guides them when necessary. “When they all sit together, many things start to happen. They become more empowered and proactive,” said Bahadur. “Through the process of making village maps, they identify who is at risk early, which is most important.” Early identification leads to early interventions – a crucial part of prevention.

“The map makes it much easier for us to keep track of the work we have to do, and how well we are doing it,” said Mamta Bagde, a senior anganwadi worker in Chhindwara’s Devgarh village. The information they collect can also reveal telling sociological trends: for instance, it’s common to see a larger number of bindis clustered in a village’s remote, segregated areas which tend to house lower-caste communities.

At AAA meetings, the health workers also compare their records of villagers’ health and vaccination requirements, correcting errors and planning their schedules for the next month. They end with a brief learning session with the Antara coordinator, evaluating their work in the previous month and discussing improvements that can be made.

In 2017, after positive feedback from AAA workers in Rajasthan’s Jhalawar district, where Antara launched its pilot, the organisation began the process of handing over its programme to the state government, which has now scaled it up to all of its 46,000 villages. This is a key part of Antara’s mission: bolstering state institutions through programmes that can eventually be sustained directly by the state.

Antara chose to focus next on Madhya Pradesh, a state that currently has the worst indicators of maternal and child health in India. As per the 2021 Sample Registration System data, MP has an infant mortality rate of 41 deaths per 1,000 births, much higher than the national average of 27. Its maternal mortality ratio is 175, compared with the national average of 93.

In MP, Antara now has field operations in 5,730 villages, engaging more than 20,000 frontline workers who serve nearly 4 lakh pregnant women and lactating mothers, and 6.5 lakh children under age five. A large portion of this population belongs to historically marginalised tribal communities.

According to the organisation, its interventions in the state have led to a three-fold increase in the identification of high-risk pregnancies, an almost two-fold rise in the number of pregnant women receiving at least four ante-natal medical check-ups, a five-fold rise in the identification of underweight children, and a 30% increase in the knowledge levels of frontline workers about maternal, neonatal and child health and nutrition.

Dr Pranjal Upadhyay, the immunisation officer of MP’s Betul district, vouched for the “tremendous impact” of the AAA platform. “Earlier, our records listed 1.13 lakh children whose immunisation was being tracked. But after the AAA workers started collating their records, we now have 1.52 lakh children registered,” said Upadhyay. Similarly, Betul district has also seen an increase in the identification and recovery rates of malnourished children. “A lot of children who were hidden are now coming under the eye of the system, which makes a huge difference.”

Antara’s commitment to effect these outcomes through institutional strengthening aligns closely with the Godrej Foundation’s approach. The Foundation believes that a key factor in India’s future prosperity and progress is a system of robust institutions that can improve access to essential services and public goods for underserved communities. Antara’s work is a meaningful example of what the work to sustain and strengthen such institutions can look like.

While its grassroots interventions have an immediate impact on communities in a limited number of districts, Antara’s model brings about long-term systemic change that can be scaled up by governments across states. It has the power to curb malnutrition and mortality among children and women nationwide, leading to a healthier and more productive population.

Early interventions, healthier outcomes

Antara’s work focuses on preventative measures, in line with its long-term goal to see reduced rates of maternal mortality, child deaths and malnutrition. Much of the impact of this work is not readily visible. Still, AAA workers in Chhindwara were eager to share anecdotes of the many instances in which they also supported children and women in potentially risky situations.

Take the case of Kavita Vishwakarma and her two-month-old baby Kunal, who come from a family of landless ironsmiths in Devgarh village. Kavita had had a high-risk pregnancy, suffering from weakness and low haemoglobin levels throughout, and Kunal weighed 2.4 kg at birth. (This was not too far below the average 2.5 kg that is considered normal birth weight in India, but unchecked, low birth weight can lead to stunted growth and even death. A 2023 study based on data from the National Family Health Survey-5, 18.2% of Indian babies have low birth weight.)

Devgarh’s AAA workers, who had been closely monitoring Kavita’s pregnancy, were quick to notice that her baby had a barely-audible voice, and insisted that he be admitted in the new-born care unit of the block-level community health centre. The baby was then moved to an incubator in the district hospital. “Within a week, his condition stabilised, and the baby now weighs a healthy 3.6 kg,” said Mamta Bagde, the anganwadi worker, smiling proudly.

According to Anjali Rai, an Antara programme officer in Chhindwara, a major part of the organisation’s efforts is to ensure that interventions take place as early as possible. “Our frontline workers try to get help for women and children at local facilities like sub-health centres early on, so that cases don’t have to be transferred to higher-level facilities unless it is absolutely necessary,” she said.

This helps to alleviate the burden on block and district-level health centres, which are already stretched beyond capacity. All of Chhindwara district has just three gynaecologists in the public sector, serving a population of 20 lakh. It’s a ratio that’s far too common across rural India. Official Rural Health Statistics data indicates that in 2021-22, there were just 1,414 gynaecologists serving 5,624 CHCs across India. To prevent unnecessary case referrals to higher-level facilities, Antara conducts periodic training sessions for ANMs and CHOs at the sub-health centre level, as well as their supervisors in the state health department, on various aspects of maternal and child healthcare.

Further up, at the block-level community health centres, it runs a rigorous nurse mentorship programme for more than 500 labour room nurses in MP. In the absence of gynaecologists at CHCs, these nurses have to handle up to three or four deliveries a day, in the presence of a non-specialist doctor. Unsurprisingly, they struggle to cope with complications in delivery, referring the case to the district hospital that may or may not have beds available at a critical moment.

The nurse mentors on Antara’s staff, who are trained nurses with field experience, address this problem by conducting frequent skill-improvement training sessions for CHC nurses. “In our trainings, we often use dummies, fake blood and role-play to simulate risky situations, so that nurses are well prepared for real cases,” said Taslima Nasrin, a nurse mentor in Chhindwara. This complements the state government’s refresher training for nurses, offered every five years, which can be relatively textbook-based. “Our training is more practical, and we cover topics that are not often covered by the state, like how to deliver a breech baby.”

Shivkumari Pal, a senior nurse at the CHC in Tamia block, says her team has been able to handle high-risk situations much better due to Antara’s nurse mentorship programme. “Just this month, we handled three breech deliveries successfully. We now know how to administer iron sucrose to mothers with low haemoglobin. Earlier, we used to refer such cases to the district hospital, but now we are making far fewer referrals,” said Pal. In Chhindwara, Antara claims its nurse mentorship programme has led to a 63% increase in the identification and management of cases of complicated deliveries.

Engaging the community

In MP, Antara has now added a new dimension to its grassroots efforts that does not involve working with state institutions: directly engaging and educating rural communities.

In 2023, Antara launched a “participatory learning action” (PLA) programme, inviting women from several villages to sign up for five-day residential training every six months, on basic aspects of maternal and child healthcare. Since then, it has trained 77 PLA facilitators, most of them housewives, who conduct monthly educational sessions in 362 villages in two districts on topics such as appropriate nutrition for pregnant women, postpartum depression, care for new mothers, and maintaining hygiene in the home.

Regular attendees at these sessions are also encouraged to participate in Antara’s new “C-AAA” model, where the “C” stands for community. With this model, AAA workers can rely on active community members for support during home visits, particularly in challenging cases where families dismiss or ignore a frontline worker’s counsel. Community members can also choose to “adopt a bindi” and take up responsibility of helping AAA workers with specific cases.

For regular participants, the PLA meetings have been eye-opening. “These meetings have helped me understand hygiene better, and how to look after my grandchildren’s health,” said Woje Kupade, a 50-year-old tribal woman from Chhindwara’s Chaukidhana village. “When saas-bahu [mother- and daughter-in-law] both attend the meetings, the saas learns that she, too, must care for her bahu.”

While community engagement programmes are taking Antara in new directions, institutional strengthening remains at the core of the organisation’s work. It involves working closely with government functionaries at all levels, which Bahadur says has been a positive experience in MP. “We have a deep respect for the experience that public servants have on the ground,” said Bahadur. “They work under very difficult circumstances, but they want to deliver outcomes.”

Over time, Antara hopes to work with several other states in India, understand last-mile problems in each instance, and offer solutions that could lead to a nationally-adaptable model of intervention in maternal and child health. As with Rajasthan, the goal in each state is to be able to eventually hand over its model to the government and withdraw its own operations as an “outsider” organisation.

“If we become redundant over time, that would be our ultimate success,” said Alexander.