Genghis Khan, much like his famed Mongol namesake, has spent a large part of his professional life fighting battles. His regular battlefield – the District and Sessions Court complex in Kollam, Kerala – is not violent or bloodied, but it is filled with the sweat of litigants and lawyers resigned to months and years of waiting for justice.

“Many of the cases I’m in charge of go on for four or five years at least,” said Khan, the general manager of the Kollam branch of a financial institution that he did not wish to name. “We even have a case pending since 2002, can you believe it?”

The cases Khan is referring to all involve cheque bouncing. His company regularly files criminal cases against clients who default on their loans through cheques that do not deliver expected payments. Cheque dishonour cases account for 10-15% of all criminal cases in Indian courts. They are not complex, intriguing or high-profile, but they make up a large share of the cases heard in magistrate courts at the district level.

In each case, once Khan and his legal team file charges under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act – the law dealing with bounced cheques – they brace themselves for a tedious legal process. It involves submitting documents and evidence, getting the papers verified, being assigned to a magistrate, issuing summons and warrants to the accused, showing up for numerous court appearances at different stages of the trial. Most of all there’s the waiting – about eight to ten weeks between each of these steps – so that the case stretches on for years. On the day that we met him, Khan said his company was juggling at least 350 ongoing cases in the Kollam court, pending for varying lengths of time.

Since November 2024, however, a small portion of Khan’s cases have been moving faster than he’d ever thought possible. They were filed not in the regular magistrate’s court but in Kollam’s unique new court set up specifically to hear cheque bouncing cases. Called the 24x7 ON Court, it is an open and networked court accessible at all hours of the day – the first digitally native avenue for justice delivery in the Indian legal system. The platform allows every step of the legal proceedings to take place digitally – from filing the case and accessing documents to the hearings themselves. In the year since it was established, ON Court has been able to dispose of most of its cases in just five or six months.

“We have filed 35 cases in the new court since last year, and 10 of them have already closed,” said Khan. “Everything is faster in this system.”

In all, 843 cases have been filed in Kollam’s ON Court in the past year, of which 151 have already been disposed of.

The 24x7 ON Court is the brainchild of the Kerala High Court, which chose Kollam district as a starting point for a pilot digital court for one specific type of case – cheque dishonour. The High Court’s knowledge partner for this court is PUCAR, a non-profit collective of organisations and individuals working to transform the way people access and experience dispute resolution. PUCAR is anchored by Agami, an organisation dedicated to legal and justice reform.

If it is successfully implemented in courts across India for cheque bouncing and other types of cases, the 24x7 ON Court model has the potential to ease the notorious problem of case pendency in courts and make justice delivery a smoother, easier and faster experience for ordinary Indians.

Digitisation versus digitalisation

For Supriya Sankaran and Sachin Malhan, the pilot 24x7 ON Court is one of the many moonshots they hoped to take for the cause of justice reform when they founded Agami in 2018. As lawyers who had also worked in other fields, they were disturbed by how daunting, onerous and inaccessible the legal system often is for the average citizen. People depend on law and justice as important tools of change, but the system itself is in desperate need of reform, re-imagination and an infusion of new ideas.

Agami works to catalyse this reformation in two parallel ways: by nurturing a strong community of diverse changemakers, or “justicemakers”, interested in improving the justice system (read more about this process here), and by co-creating “missions” or platforms for tangible reform on the ground, such as Online Dispute Resolution, OpeNyAI, and PUCAR – all using digital platforms in different ways to create change.

India’s existing e-Courts platforms, at the Supreme Court, High Court and district court levels, have computerised a range of court proceedings. Introduced in phases from 2007, the e-Courts portals allow citizens to view (among other things) cases listed for hearings on any given day, case status and basic case details, as well as orders and judgements scanned and uploaded into the system.

But PUCAR’s vision was to move beyond the simple digitisation of courts towards digitalisation – that is, not merely uploading information from paper to digital platforms, but using technology to re-engineer, end-to-end, how courts function.

“The idea behind PUCAR was to transform the dispute resolution process to become people centric,” said Sankaran. “Incremental improvements to colonial processes designed 100 years before will not help us get there. We need to fundamentally imagine new possibilities. So we asked ourselves: if we were to set up a court from scratch today, with modern technology, what would it look like?”

As the unit of transformation, PUCAR selected high-volume and low-complexity disputes like cheque dishonor (criminal) and motor vehicle compensation (civil) cases, which comprise 20% of the pendency in Indian courts. This allowed them to reimagine the process right from the start of the dispute up to the recovery of money from the perspective of the complainant.

In 2023, Sankaran had the opportunity to present PUCAR’s ideas before an E-Committee appointed by the Supreme Court, which gave the collective an in-principle approval to develop a workable solution to transform justice delivery in cheque bouncing and motor vehicle cases in the states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Delhi. It authorised Computer Committees in each state’s High Court, to launch new courts meant to steer this transformation. In early 2024, the High Court of Kerala proceeded to launch the first 24x7 ON Court in Kollam district in partnership with PUCAR.

To effectively diagnose, design and implement the court, PUCAR leveraged the collective strengths of its member organisations. For instance, the XKDR Forum, a non-profit research think tank, conducted an in-depth study into cheque dishonour cases in order to identify where cases got stuck. It found that the majority of cases get delayed even before they reach the trial stage in a courtroom. Once trials for cheque bouncing cases begin, cases tend to be resolved within four months. But these cases often spend up to 12 months in the pre-trial stage, largely because of the difficulties in getting both parties, particularly the accused, to show up in court. Other behind-the-scenes administrative work, like filing documents, maintaining records and scheduling hearings, creates further delays.

Agami then brought together diverse innovator communities needed to implement the 24x7 ON Court. The E-Government Foundation brought its expertise in designing and creating the digital infrastructure, and Samagra, a governance consultancy firm, took charge of programme management and implementation.

How the digital court works

In a typical cheque dishonour case, the aggrieved party first sends a demand notice, via post, informing the accused that their cheque has bounced. If the accused does not respond within 30 days of receiving the notice, a case can be filed directly with the magistrate court. From this very point, the 24x7 ON Court offers a faster and more accessible route to justice than the traditional method.

On its portal, where lawyers and litigants can both create their accounts, a cheque bouncing case can be filed directly, through an online form, without needing to visit the court. The court fees and other payments can also be made online, and any signatures required can be done digitally, through Aadhaar-based authentication. All relevant documents, once uploaded on the portal, may be accessed by all parties, including the magistrate, without the need for resubmission or duplication during different stages of the trial. Summons, too, can be issued to the accused digitally, via text and email, which is faster than the traditional process of sending summons through the post. The accused can respond to the digital summons by submitting their own documents online, speeding up the pre-trial process.

One of the biggest advantages of the portal, according to several lawyers, is that it allows for “asynchronous” submission of documents. In regular courts, all petitions, forms and evidence must be submitted as hard copies within specific work hours – 10 am to 5 pm – a day before they are required by the court. “If for any reason you miss this deadline, you have to file a delay petition and the whole process gets delayed by a few days,” said Beena M, a senior advocate and mediator at the Kollam district court. The 24x7 ON Court allows document submission at any time of the day or night, which is a relief for lawyers who juggle dozens of case deadlines on a daily basis.

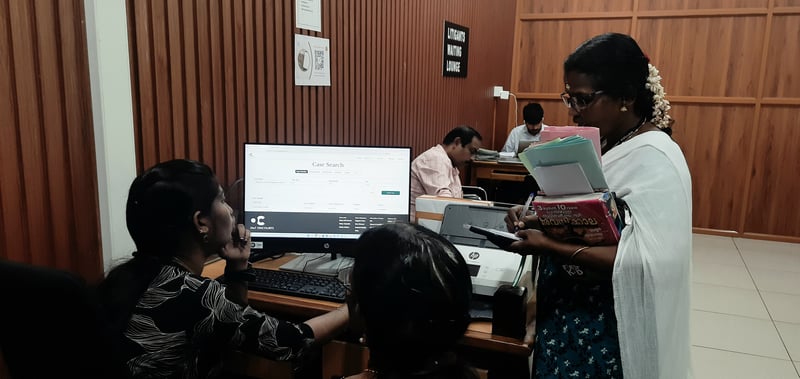

The ON Court portal has a clean, intuitive and user-friendly interface, and when it was launched, the PUCAR team provided lawyers some basic training on how to use it. However, in the spacious, wood-panelled ON Court office within the premises of the Kollam court, there is an E-Seva staff member available regularly for those who need help navigating the site.

The E-Seva officer is, in fact, one of just four staff members needed by ON Court apart from the magistrate. The other staff members include a junior superintendent, a bench clerk and a stenographer. While they were not authorised to give official statements, their informal conversations with us highlighted how the online court had eased their administrative burdens significantly.

The junior superintendent’s main role, for instance, is to scrutinise and verify all documents submitted by litigants at the start of a case. On the ON Court portal, the system automatically validates information, matches dates, and highlights discrepancies that need correction. This saves the scrutiny officer hours of tedious work.

After documents are verified, the portal assigns the case to the magistrate, creates a daily schedule of hearings, and at every stage, sends out automatic notifications to both litigants and lawyers about the date and time of each hearing, and about action required at each point.

In regular courts, judges typically have 150-200 hearings a day, including short court appearances for procedural matters. Every evening, it falls to the bench clerk to pull out paperwork for the next day’s cases from rooms full of thousands of files. If any papers or files go missing or are misplaced – which happens quite often – the bench clerk could be punished with brief suspension. The ON Court circumvents this strenuous labour and risk: all case files are readily available on the portal.

To improve user experience, the PUCAR team closely monitors details like the number of clicks needed for staff to reach from point to point within the portal, and identifies ways to reduce the steps. “We have tried to design an experience that is seamless for court staff and litigants,” said Mehul Sehgal, a Samagra member and manager of the ON Court programme team.

In its baseline study of cheque bouncing cases, XKDR had found that the filing, registration and cognizance of cases in regular courts take an average of 160 days. ON Court – which has a live public dashboard to monitor its progress – takes less than 50 days for these steps. At the summons and warrants stage, ON Court takes just 60 days instead of the 300 days taken in regular courts. And at the trial stage, 98% of the hearings take place as scheduled in the digital court, as opposed to 40% in traditional courts.

While the portal allows for trials to take place entirely online, through video conferencing, most hearings take place in a special courtroom attached to the ON Court office. The only air-conditioned courtroom in the Kollam district court complex, it is fitted with multiple large screens. The magistrate and court staff use the portal during hearings not only to access documents but also take notes and prepare orders with the help of available templates. Video conferencing is always active, in case any of the parties choose to attend online. This option, according to the court staff, is particularly helpful for litigants who may be living in other cities or countries, and cannot afford to keep travelling to Kollam for hearings (another reason why cases in traditional courts often face delays).

Many lawyers prefer to attend ON Court hearings in-person because they are already in the district court for several other cases in regular courts. “Sometimes, there are also technical glitches with the video calls, making it risky,” said Venugopal, an advocate in the Kollam court. “If I miss a hearing just because of a tech problem, I lose my chance to have a hearing that day.”

Technical problems aren’t unheard of. Lawyers can face issues like glitches during video calls and errors in digital payments while using the ON Court portal. To address them, PUCAR has instituted an active feedback mechanism, and a team from Samagra is stationed in Kerala to review problems, design solutions and update the portal in collaboration with the High Court’s technical directorate in Kochi.

Speedy justice

Lawyers and litigants repeatedly emphasised, however, that the pilot digital court has succeeded in its main objective: providing speedy justice delivery.

“This is the main advantage of ON Court – unlike other courts, there are no lags that go on for years,” said senior advocate Asha GV, one of the first lawyers to file a case on the portal in November last year. In traditional courts, there is an average gap of two or three months between each hearing in a case trial. “But here, hearings in each case happen every two weeks, so cases get disposed of within six months.”

In any court, cases can be disposed of in multiple ways – either ending in a judgement (conviction or acquittal), dismissal (if the judge finds it lacks merit), or withdrawal by the complainant. In the 24x7 ON Court, 87% of the disposed cases have been withdrawn, often because litigants agree to an out-of-court settlement through mediation.

According to Praachi Bhatia, a consultant from Samagra, there is a high number of case withdrawals in the ON Court system because arrest warrants are issued faster when the accused fail to respond to summons. “In regular courts, there are three to four rounds of summons before warrants are issued. But when escalation happens faster, parties are more willing to settle,” said Bhatia.

“For us, this means that the bulk of the cases we file get settled in months instead of years,” said Ajarsha LR, the legal manager of HDFC Bank’s Kollam branch. As a financial institution, it has filed dozens of cheque bouncing cases in the ON Court in the past year, and is very satisfied with its impact. “When our cases get resolved faster, we get our money back from the accused faster.”

Can the success of this pilot court be easily replicated and scaled up? In Kollam, the district court was able to provide the infrastructure for the ON Court and also assigned a dedicated magistrate to hear its cases. According to the PUCAR team in Kerala, bar associations in other parts of the state have also expressed an interest in having an ON Court in their districts. Even if these special courts were to focus solely on cheque dishonour cases, court staff and lawyers in Kollam believe it could help reduce overall case pendency in the system.

For both PUCAR and Agami, however, the long-term vision is to be able to create similar digitally native courts across India, and extend it to other disputes beyond cheque bouncing cases.

“The pilot 24x7 ON Court has been able to lay the foundation for systemic transformation of court processes,” said Agami’s Supriya Sankaran. “We are using technology to simplify core processes, which can be adapted for other courts and dispute types – the technology is open and available for others to adopt, so that courts can be transformed at a wider scale.”